Bills to shed light on newborn DNA storage in California quietly killed or gutted

If you're related to someone who was born in California since 1983, a portion of your DNA is likely in the state's massive Newborn Genetic Biobank. In response to our decade-long investigation, lawmakers have introduced several bills intended to shed light on how the state is amassing and using California's newborn DNA stockpile.

Only one of those bills is still alive, and while privacy advocates say it is a step in the right direction, recent amendments raise new questions about the appearance of state secrecy.

CONTINUING COVERAGE: Investigating Newborn Blood Spot Privacy Concerns

(To learn more about newborn bloodspot storage and how to opt out of storage or research, click here.)

A life-saving test

Every baby born in California gets a heel prick shortly after birth. Their newborn blood fills six spots on a special card which is used to test them for genetic disorders that, if treated early enough, could prevent severe disabilities – even death.

Doctors only need a few of the baby's newborn bloodspots for their own life-saving genetic test. The leftovers become the property of the state and are stored indefinitely in California's massive Newborn Genetic Biobank.

What happens next has become a state secret.

California State Secrets

According to the state, there has never been an outside audit of how California's stored newborn DNA samples are being used by the state, law enforcement, or independent researchers.

Throughout our decade-long investigation, CBS New California has reported on multiple law enforcement requests for identified newborn bloodspots, and the thousands of de-identified DNA samples that are sold each year to independent researchers.

For years, we've obtained those records from the state under California's Public Records Act. The records have enabled us to show the public how our DNA is being used and highlight the program's lifesaving benefits.

However, following the pandemic, the California Department of Public Health suddenly started refusing to disclose who is requesting California's stored newborn DNA samples and why.

The agency told CBS News California that it "is no longer tracking" that information like it used to and is "not required to create a record" revealing who has access to our DNA.

Playing Politics with Newborn DNA

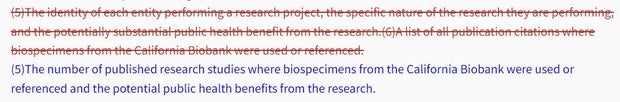

In response to our reporting, SB 1099 would have required the California Department of Public Health to publicly identify "each entity performing a research project, the specific nature of the research they are performing, and the potentially substantial public health benefit from the research."

With no formal opposition or significant cost, the bill has sailed through the legislature with widespread support, and it is expected to head to the governor's desk.

However, after the bill passed the Assembly, it was recently amended in the state Senate where lawmakers agreed to remove the part of the bill that requires the state to reveal who is using our DNA for research and why.

Instead, the bill now only requires the state to reveal the number of published studies and the number of California DNA samples used for research.

Privacy advocates say that is a small step in the right direction, but they question the continued state secrecy.

Calls for transparency

While California's Newborn Genetic Biobank program has undoubtedly saved lives, the appearance of state secrecy raises concerns.

For years, everyone from privacy advocates to lawmakers has called for more transparency.

"People (should) have the right to choose how their DNA is used and how their children's DNA is used," said Cece Moore, a genetic detective, in a previous interview.

"What are they trying to hide?" asked Consumer Watchdog's Jaime Court.

ALSO READ: Lawmakers could force California to stop storing your DNA without permission

Parents are in the dark

California has been storing newborn blood spots since 1983 and has amassed what's believed to be the largest stockpile of newborn DNA samples in the country because it's one of only a handful of states that stores the bloodspots indefinitely without parents' permission.

You can ask to have your child's DNA sample destroyed or opt out of storage for research after your DNA is collected and stored. However, you'd have to know the state was storing your child's bloodspot in the first place, and most parents don't know.

(To learn more about newborn blood storage and how to opt-out of storage or research, click here.)

California's Genetic Information Privacy Act requires consumer companies like 23andMe to get your permission before they store, use, or sell your DNA. However, your state government is exempt from that law, and there has never been an outside review or audit of how your DNA is being used.

In 2015, former Assemblyman Mike Gatto was the first to author a bill intended to increase transparency related to the Newborn Genetic Biobank. The bill would have allowed parents to opt out of bloodspot storage for research before the bloodspots were stored. It passed the Assembly and died in the Senate.

"There is no reason to be doing experiments on a child's blood without informed consent," Gatto said.

Over the years, the powerful medical lobby killed several bills that would have allowed parents to consent to storage and research. They argued that if given the choice, too many parents would opt out of storage, which could ultimately harm potentially life-saving research.

However, earlier this year, the medical lobby appeared to change its stance following amendments to another newborn genetic transparency bill, SB 625.

When the author agreed to amend the bill to allow parents to "opt-out" of storage instead of allowing them to "opt-in," the medical lobby removed its opposition and changed its stance to "neutral."

However, it was quietly killed behind closed doors without a vote in the Senate Appropriations suspense file because California's Health Department argued it would cost too much to give parents that right.

Privacy advocates plan to try again next year.

Find out if researchers have requested your child's newborn bloodspot

Parents do have the right to find out if their own child's bloodspots are being used for research and they can request the state destroy their child's sample after it is stored.

You can find more information about your rights here.