As many kids fall behind, schools try a new approach to teach how to read

Only about one-third of elementary school students in the U.S. are reading at grade level, according to the recent National Assessment of Educational Progress. In response, many schools are rethinking how they teach kids to read.

In one New York City first grade classroom, Melissa Vega-Jones goes letter by letter, teaching the specific rules that form the English language. For decades, most schools felt it was unnecessary to explicitly teach kids these rules, preferring to give students time with books on the belief they would most likely figure it out for themselves.

Now, specific, detailed instruction is taking over.

"It was a big shift in my teaching, in my understanding of how students learn to read," Vega-Jones said.

The Science of Reading isn't so much a curriculum as a grassroots movement best known for arguing that phonics, or the relationship between letters and their sounds, is key to learning to read.

It's powered by parents who believe the old system left their kids behind, and the movement is quickly transforming how reading is taught.

In 39 states and Washington, D.C., laws have been passed or rules have been made requiring schools to follow the Science of Reading approach.

That generally means new books and new teacher training with a focus on phonics.

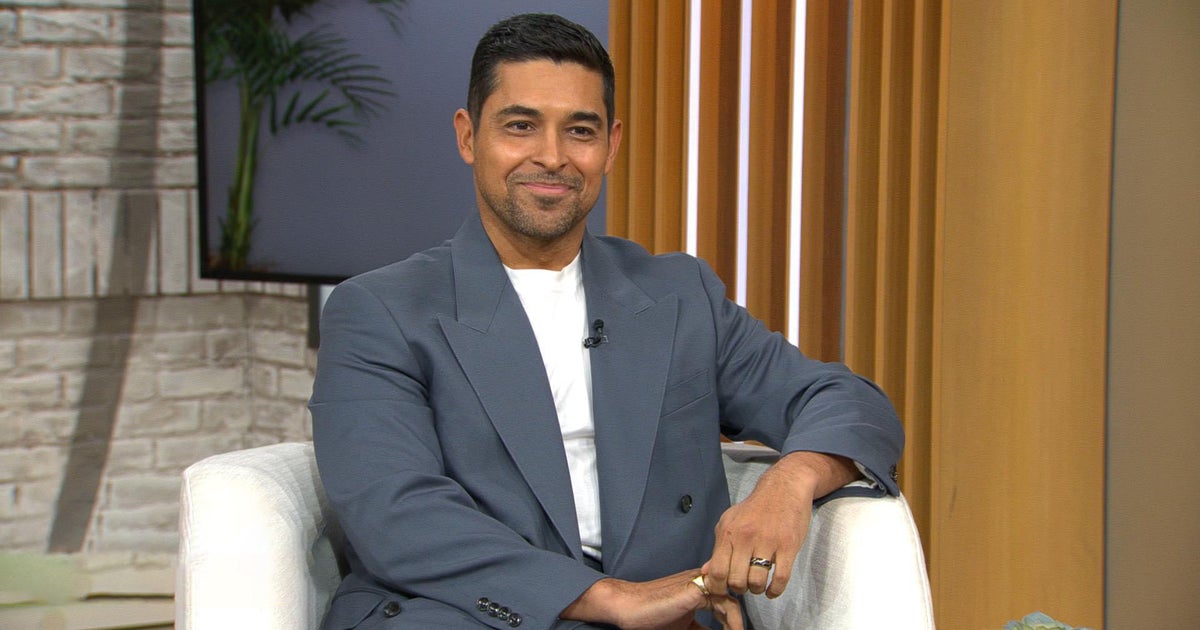

Jason Borges is overseeing New York City's new reading program, which began with a partial rollout last year and will be in every classroom this fall.

"What we were doing was not working," Borges said. "Fifty-one percent of students are not at proficiency and not close to proficiency."

As the new methods take over, old approaches like queuing —where kids look at pictures in a book to guess the word— are being pushed out.

Instead, when students flip through picture books, they're now taught to ignore the pictures and focus instead on the letter groups.

Research is showing the new method helps, but somewhat modestly. A recent Stanford study found two years of the approach was like getting an extra quarter-year of learning.

Implementing the changes can also be hard, and knowing just how far to push those changes is still being worked out.

"It's not just about phonics, right? There's so much more to teaching reading that I worry that things will be not only too reductive, being just phonics, but then also that things do get taken a bit too far," Borges said.

The nation's largest school system is attempting that balance, and the test results will be eagerly awaited.

Editor's note: This article has been updated to correct Melissa Vega-Jones' last name.