Goa scientists find 50,000-year-old magnetic fossils in Bay of Bengal

[ad_1]

Needle, spindle, bullet and spearhead shape-magnetofossils.

| Photo Credit: Kadam, N et al/Nature

In the depths of the Bay of Bengal, scientists have discovered a 50,000-year-old sediment — a giant magnetofossil and one of the youngest to be found yet.

What are magentofossils?

Magnetofossils are the fossilised remains of magnetic particles created by magnetotactic bacteria, also known as magnetobacteria, and found preserved within the geological records.

Magnetotactic bacteria are mostly prokaryotic organisms that arrange themselves along the earth’s magnetic field. These unique creatures were first described fairly recently, in 1963, by Salvatore Bellini, an Italian doctor and then again in 1975 by Richard Blakemore of the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, Woods Hole, Massachusetts.

These organisms were believed to follow the magnetic field to reach places that had optimal oxygen concentration. Using an electron microscope, Blakemore found the bacteria contained “novel structured particles, rich in iron” in small sacs that essentially worked as a compass.

These magnetotactic bacteria create tiny crystals made of the iron-rich minerals magnetite or greigite. The crystals help them navigate the changing oxygen levels in the water body they reside in.

The fossils left behind by the crystal-creating bacteria help scientists glean conditions that prevailed millions of years ago and which contributed to “the sediment magnetic signal”.

What makes the Bay of Bengal sediment special?

In previous studies on magnetofossils often ascertained their origins to be hyperthermal vents, comet impacts, changes in oceanic ventilation, weathering or the presence of oxygen-poor regions.

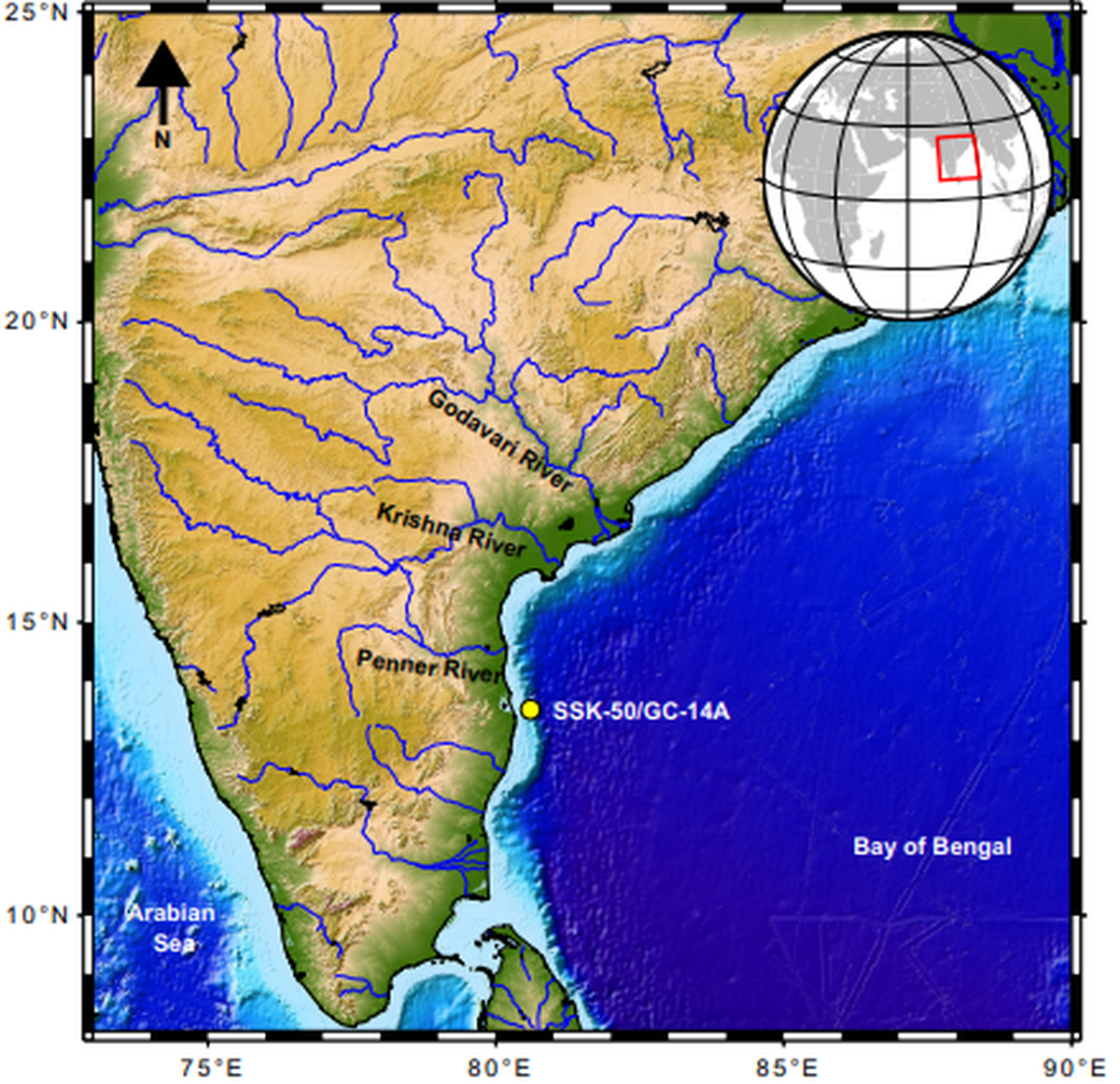

Sediments deposited at the core site originate predominantly from the Godavari, Krishna, and Penner Rivers, highlighted on the map.

| Photo Credit:

Kadam, N et al/Nature

In fact, the origin of giant magnetofossils has stayed a mystery. Most giant magnetofossils have been found in sediments dating to the late Palaeocene period, some 56 million years ago, suggesting they formed only during periods of extreme warming.

But in the new study, published in the journal Nature in February, the scientists found the sediment in the Bay of Bengal to be from the late Quaternary period, or about 50,000 years ago, making it the youngest giant magnetofossil to have been found found yet.

What did the study find?

In the study, scientists at the CSIR-National Institute of Oceanography, Goa, combined magnetic analyses and electron microscopy to study the sediment sample.

The three-metre-long sediment core from the southwestern Bay of Bengal consisted mainly of “pale green silty clays,” they wrote in their paper. They also reported finding abundant benthic and planktic foraminifera — single-celled organisms with shells found near the sea bed and free-floating in water.

High-resolution transmission electron microscopy revealed the fossil to be in the shape of needles, spindles, bullets, and spearheads. The microscopy also confirmed the presence of ‘conventional’ magnetofossils along with giant ones.

At a depth of around 1,000-1,500 m, the Bay of Bengal has a distinctively low oxygen concentration.

Earlier, studies of sediments suggested that nearly 29,000 to 11,700 years ago, during the last Glacial Maximum-Halocene period, the northeast and southwest monsoon strengthened and resulted in significant weathering and sedimentation.

Analysis of the sediment sample confirmed fluctuations in the monsoon took place as the scientists found particles of magnetic minerals from the two distinct geological periods.

The scientists also suggested the rivers Godavari, Mahanadi, Ganga-Brahmaputra, Cauvery, and Penner, which empty into the Bay of Bengal, played a crucial role in the formation of the magnetofossils.

The nutrient-rich sediment carried in by these rivers provided a sufficient supply of reactive iron, which combined with the available organic carbon in the suboxic conditions of the Bay of Bengal to create a favourable environment for the growth of magnetotatic bacteria.

The freshwater discharge from these rivers along with the other oceanographic processes, like eddy formation, rendered the oxygen content in these waters that isn’t usually found in other low-oxygen zones.

The scientists also said the presence of the magnetofossils showed that the suboxic conditions of the Bay of Bengal persisted for a long time, allowing the bacteria to thrive.

[ad_2]

Source link